I hope you’ll click through to my post at the Nerdy Book Club to see the cover for my new book, which is due out September 5th. I hope you like it!

A Bad Air Day

You may have seen recent news reports about London’s dangerous air quality.

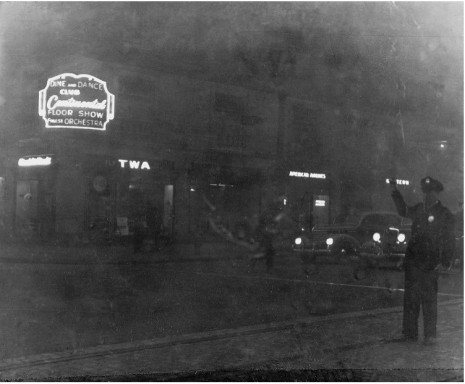

In light of the current political climate in the U.S., I thought it might be timely to re-post a blog I wrote a few years ago about the history of air pollution here in the United States. It shows pictures of what Pittsburgh and Saint Louis looked like prior to the smoke control ordinances of the mid-1940s.

The EPA is a vital organization. I fear for its future.

On Friday I blogged about the Donora Death Fog of 1948, and alluded to the city of Pittsburgh’s smoke control ordinances. Pittsburgh’s amazing turnaround will be the subject of today’s blog.

My parents met one another when they were both in graduate school at the University of Pittsburgh, just after World War II. I knew from having researched sanitation and pollution that Pittsburgh was once a very smoky city, but I didn’t make the connection until just recently that my parents lived there during the smoky time. And I had no idea just how smoky the city actually was. I contacted the University of Pittsburgh Archives Center, and they very kindly gave me permission to reprint these pictures from the late 30s and early 40s. They’re kind of amazing.

What’s incredible to realize is that these pictures were shot during the daytime.

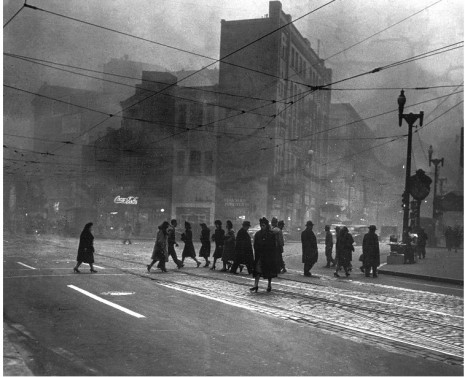

This one shows a street scene in St. Louis, which is where the smoke control ordinance was first enacted and upon which the Pittsburgh program was based.

According to the University of Pittsburgh website, the smoke control ordinances regulated the burning of coal by locomotives, the steel industry, and individual citizens. The city had been trying since 1807 to control the smoke, but for decades, people believed that heavy smoke in the air indicated high productivity. They also thought smoke was good for the lungs and for the crops. So legislation wasn’t enforced until after World War II.

According to the University of Pittsburgh website, the smoke control ordinances regulated the burning of coal by locomotives, the steel industry, and individual citizens. The city had been trying since 1807 to control the smoke, but for decades, people believed that heavy smoke in the air indicated high productivity. They also thought smoke was good for the lungs and for the crops. So legislation wasn’t enforced until after World War II.

This final shot is quite extraordinary, and eerily beautiful. The Heinz History Center gave me permission to run it. Remember: it’s daytime.

Downtown Pittsburgh at 9:20 a.m. in the fall of 1945, before smoke control Library and Archives Division, Historical Society of Western Pennsylvania, Pittsburgh, PA

On Wednesday’s blog–the deadly London Fog of 1952.

Santa’s Evil Sidekick

Loyal readers may have noticed that I haven’t been posting very frequently recently. That’s because I have a looming book deadline (January 25th, to be exact). But as it’s the holidays, I thought I’d repost this piece I did a few years ago about the history of Santa-figures in other countries:

As a mother, I freely admit to having played the Santa card when my kids were younger. “Better stop fighting you guys. Santa is watching!” For years, that tactic scared them into submission and good behavior, at least around holiday time. But that type of psychological manipulation is pretty tame stuff, compared with what kids have had to endure in other places and times.

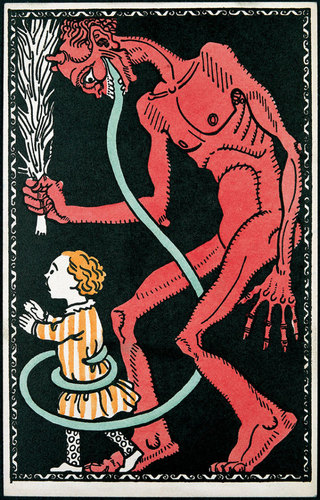

Recently I did a post about the special genre of nineteenth century children’s books that taught morality and manners to children. The general idea behind these books was to scare kids witless in order to get them to behave. Today’s post is a holiday version of that genre; the various European traditions that turned Christmas into a form of Judgement Day. Good kids would get presents. Bad kids got punished in various creative and harrowing ways.

Recently I did a post about the special genre of nineteenth century children’s books that taught morality and manners to children. The general idea behind these books was to scare kids witless in order to get them to behave. Today’s post is a holiday version of that genre; the various European traditions that turned Christmas into a form of Judgement Day. Good kids would get presents. Bad kids got punished in various creative and harrowing ways.

This article in the New York Times breaks down some of these mostly-European Christmas traditions. In Iceland, naughty children were carted off by two thirteenth-century ogres and eaten. In Greece, mean imps jumped onto kids’ backs and forced miscreants to dance til they dropped. In France, Father Christmas (Pere Noel) had an evil sidekick named Pere Fouettard (loosely translated as “Father Spank-you.”)

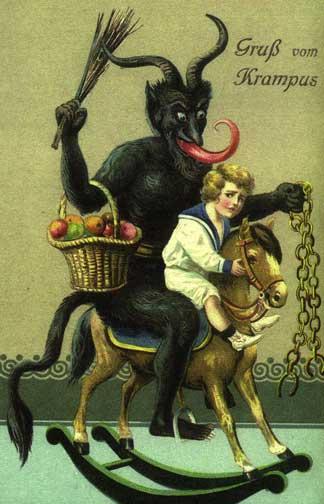

But for me, at least, the scariest is Krampus. He’s a demonic character from folklore common in Austria, the Netherlands, and Switzerland, with horns, hooves, and a long tongue. According to legend, Krampus joined Saint Nicholas on his Christmas rounds. While jolly old Saint Nick doled out gifts to the good kids, Krampus dispensed coal and swatted the pretty-bad with ruten bundles (birch branches), and then stuffed the especially naughty kids into his gunnysack and hauled them away, presumably to be eaten for his Christmas dinner.

But for me, at least, the scariest is Krampus. He’s a demonic character from folklore common in Austria, the Netherlands, and Switzerland, with horns, hooves, and a long tongue. According to legend, Krampus joined Saint Nicholas on his Christmas rounds. While jolly old Saint Nick doled out gifts to the good kids, Krampus dispensed coal and swatted the pretty-bad with ruten bundles (birch branches), and then stuffed the especially naughty kids into his gunnysack and hauled them away, presumably to be eaten for his Christmas dinner.

Images:

Top: a Greeting Card from the Krampus 1900 via Wikimedia

Middle: Krampus and Saint Nicholas in a Viennese home, 1896,

Bottom: an early twentieth century Krampus card

Shoddy Shoddy

![By Tim Green from Bradford (Shoddy & Mungo) [CC BY 2.0 (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0)], via Wikimedia Commons](https://www.sarahalbeebooks.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/10/Shoddy__Mungo_8044403863-450x360.jpg) Nowadays the word “shoddy” means something that is cheap and poorly made and liable to come apart. The origins of the word date back to the 19th century. “Shoddy” (a noun) was a type of fabric made by grinding up old woolen rags and mixing them with fresh wool. (“Mungo” was similar but of somewhat higher quality.) The shredded stuff was re-spun and re-woven into new material. The process was invented in England in 1813. Rag sorters picked through and sorted dirty, grimy rags according to quality and color. The grinding process created enormous amounts of dust.

Nowadays the word “shoddy” means something that is cheap and poorly made and liable to come apart. The origins of the word date back to the 19th century. “Shoddy” (a noun) was a type of fabric made by grinding up old woolen rags and mixing them with fresh wool. (“Mungo” was similar but of somewhat higher quality.) The shredded stuff was re-spun and re-woven into new material. The process was invented in England in 1813. Rag sorters picked through and sorted dirty, grimy rags according to quality and color. The grinding process created enormous amounts of dust.

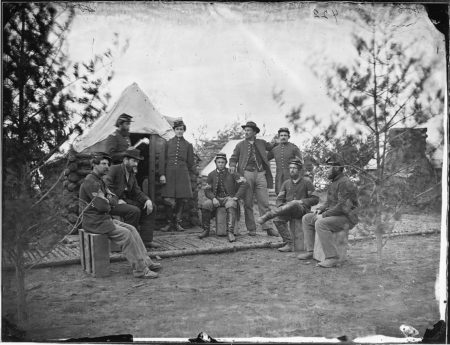

Shoddy made clothing much less expensive. But some manufacturers cheated their customers by supplying super-shoddy, er shoddy. During the American Civil War there was a huge demand for woolen cloth for uniforms. Suppliers out to make a quick buck supplied shoddy shoddy that was of such poor quality, soldiers’ uniforms fell apart after a few wearings.

sources:

http://www.maggieblanck.com/Land/Shoddy.html

http://www.archive.org/stream/technologyquart05techgoog#page/n99/mode/1up

photos:

Top: Tim Green from Bradford (Shoddy & Mungo) [CC BY 2.0 (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0)], via Wikimedia Commons

Bottom: Brady National Photographic Art Gallery (Washington, D.C.) (1858 – ?), Photographer (NARA record: 1135962)

Eleanor and the Troubadours

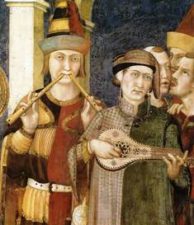

I’ve been reading a biography of Eleanor of Aquitaine (1137-1152), which led me to the subject of troubadours.

Troubadours were poets and musicians whose art form flourished mostly between the 11th and 13th centuries. They tended to be employed by a wealthy person, often for their whole careers, and mostly in the Provence region of medieval France. The subject of their lyric poetry was often about unrequited love, the love-sick poet pining for an unattainable lady. Every college English major knows this literary convention as “courtly love.”

Troubadours were poets and musicians whose art form flourished mostly between the 11th and 13th centuries. They tended to be employed by a wealthy person, often for their whole careers, and mostly in the Provence region of medieval France. The subject of their lyric poetry was often about unrequited love, the love-sick poet pining for an unattainable lady. Every college English major knows this literary convention as “courtly love.”

So what does all this have to do with Eleanor? One of the first famous troubadours was her grandfather, William of Aquitaine (1071 – 1127), who composed some pretty racy verse. This is but one cool fact about one of western Europe’s coolest women ever.

Eleanor would eventually become queen of two kingdoms (first France, then England), and mother of two kings. At fifteen, the fabulously wealthy Eleanor married her first husband, Louis. Soon to be crowned Louis VII, he was a super-religious dullard who worshipped his wife—from afar. His father died soon thereafter, and the couple was crowned king and queen of France.

Eleanor was bored with palace life. To give you an idea of the castle’s lack of creature comforts, a fireplace was installed after she moved in, to modernize it.

She had two daughters as queen of France, but she and Louis became increasingly estranged, and finally the Pope agreed to annul their marriage. Two months later, Eleanor married Henry, Count of Anjou and Duke of Normandy. Two years after that, they were king and queen of England. They had eight children together, but in 1167, they separated, possibly because of Henry’s multiple infidelities. Eleanor moved back to her own turf in Poitiers, and established The Court of Love, where she patronized artists and poets and the arts.

There’s so much more to her amazing life, but I wanted to focus on the troubadours and Eleanor’s role in their place in history.

Back in the English court, Eleanor had encouraged troubadours, which soon became part of medieval English society. One of the finest troubadours was Bernard de Ventadour, (sometimes spelled Bernart de Ventadorn). Eleanor brought him to the English court, where he composed cool stuff like this. He and Eleanor may also have had a love affair (some historians think it happened after her marriage to Louis ended and before Henry). Suffice to say, when he returned from a sojourn around his kingdom, Henry didn’t seem psyched to see the troubadour settled in at his English court.

Two summers ago I visited the abbey at Fontevraud, where Eleanor is buried. Here’s a patch of loveliness outside the abbey:

And here’s a picture I took of her, lying next to Henry. I love that she’s depicted reading a book. Their son, Richard the Lionheart, is also entombed there, or at least most of him is. His heart and other entrails were sent to a couple of other cathedrals in France.

Incidentally, there is a difference between a troubadour and a wandering minstrel. Here’s Monty Python’s example of the latter.

http://www.medieval-life-and-times.info/medieval-music/troubadours.htm

http://www.medievalists.net/2015/01/29/troubadours-part-sad-songs-say-much/

The Schuylers

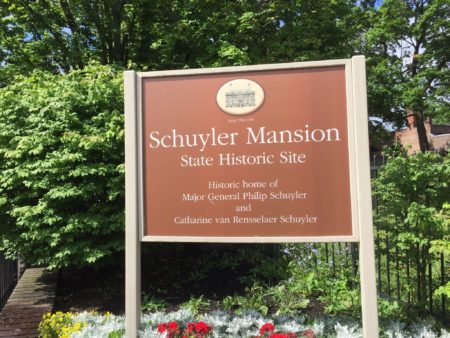

Last week I drove to upstate New York for my annual writing retreat. On the way, I stopped off at the Schuyler Mansion in Albany. Philip Schuyler and his wife, Catharine van Rensselaer, lived in this house with their eight children. (They had a set of twins and a set of triplets that did not survive.) The eldest surviving child was Angelica. Another daughter, Eliza, married Alexander Hamilton. I’m researching Hamilton for an upcoming project. Have I mentioned I have the best job in the world?

Last week I drove to upstate New York for my annual writing retreat. On the way, I stopped off at the Schuyler Mansion in Albany. Philip Schuyler and his wife, Catharine van Rensselaer, lived in this house with their eight children. (They had a set of twins and a set of triplets that did not survive.) The eldest surviving child was Angelica. Another daughter, Eliza, married Alexander Hamilton. I’m researching Hamilton for an upcoming project. Have I mentioned I have the best job in the world?

There were only seven of us on the tour—me, a couple from Saratoga, and a family of four with two charismatic kids. The boy knew a lot about Revolutionary war battles, and the girl seemed interested in everything, which was a good thing, because I may or may not have co-opted the tour. Danielle, our tour guide, was wonderful and knowledgeable, but I always feel bad for tour guides when a writer, for instance, me, shows up for a tour. Obviously I didn’t feel bad enough, because I pestered Danielle with questions.

Unfortunately all the most interesting stuff (to me) about the house has not survived—namely, the slave quarters, the kitchen, and the necessary. But Danielle knew a lot about them, and answered my questions. And it was exciting to see the original portraits of Eliza

And Angelica (here she is with one of her ten children): It was cool to see field beds that can be broken down for travel, along with a bed key:

It was cool to see field beds that can be broken down for travel, along with a bed key: Danielle obligingly held up a jar of leeches from Philip’s medical kit, so I could photograph it.

Danielle obligingly held up a jar of leeches from Philip’s medical kit, so I could photograph it.

And here’s what may or may not be a cut from a sword or tomahawk on the banister.

And here’s what may or may not be a cut from a sword or tomahawk on the banister.  In 1781, a band of British soldiers and local loyalists, operating out of Canada, attempted to kidnap Philip Schuyler. In one version of the story, which Danielle says is difficult to verify, Peggy had just grabbed her baby sister Catharine from the cradle, en route to fleeing upstairs with her, when someone threw a tomahawk at her and missed.

In 1781, a band of British soldiers and local loyalists, operating out of Canada, attempted to kidnap Philip Schuyler. In one version of the story, which Danielle says is difficult to verify, Peggy had just grabbed her baby sister Catharine from the cradle, en route to fleeing upstairs with her, when someone threw a tomahawk at her and missed.

Here’s another version of the thwarted kidnap attempt, which doesn’t include the dramatic last-minute rescue of a baby, but is still pretty exciting.

Behind the Curtain

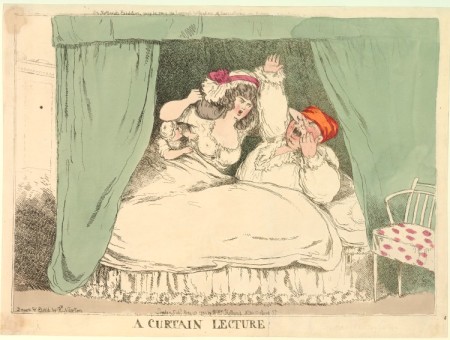

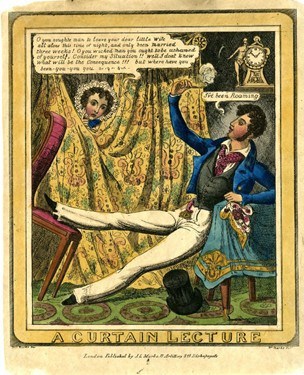

Have you ever heard of a “curtain lecture?” (The above image isn’t actually a curtain lecture. I just liked the image.)

A “curtain lecture” (sometimes called a “bolster lecture”) is a private reprimand given by a wife to her husband. Back in the days when a bed was often a family’s most valuable possession, many were four-poster types with thick curtains. The curtains kept away drafts, and also, according to generations of male writers, allowed the wife to scold her husband in privacy.

I actually stopped at this reference and wondered about it when I recently read Dicken’s Our Mutual Friend:

‘You are just in time, sir,’ said Bella; ‘I am going to give you your first curtain lecture.’

A search for the term in literature calls up dozens of examples, and they go way back. Here’s one from 1640, in the the book Ar’t Asleepe Husband? A Boulster Lecture by Richard Brathwait. Brathwait is going for levity. A wife’s admonitions, he assures the reader, are meant to be dismissed as random background noise :

This wife a wondrous racket meanes to keepe,

While th’Husband seems to sleepe but do’es not sleepe:

But she might full as well her Lecture smother,

For ent’ring one Eare, it goes out at t’other.*

Ha ha LOL. And here are some images of curtain lectures, all of course rendered by male artists.

From Thomas Heywood’s A Curtaine Lecture, 1637 The text says: When wives preach, tis not in the Husbands power to have their lectures end within an hower. If Hee with patience stay till shee have donn. Shee’l not conclude till twyce the glass Hee runn.

*As quoted in Sloan, LaRue Love, “I’ll watch him tame, and talk him out of patience”: The Curtain Lecture in Shakespeare’s Othello. Lamb, Mary Ellen, Bamford, Karen, eds. Oral Traditions and Gender in Early Modern Literary Texts. Burlington, VT: Ashgate, Publishing, 2008, p 88.

Theodosia and Theodosia

Fans of the Broadway show, Hamilton, will be familiar with the beautiful duet, Dear Theodosia, sung by Aaron Burr (Leslie Odom Jr.) and Alexander Hamilton (Lin-Manuel Miranda). It’s an ode to their newborn babies, Theodosia and Philip. (You can listen to it here.)

Earlier in the play, in the Story of Tonight reprise, Burr had confessed to Hamilton that he’d been having an affair with the wife of a British officer. That would be Theodosia’s mother, Theodosia. Let’s investigate the history behind this:

During the war, Aaron Burr was the aide-de-camp to General Israel Putnam, Washington’s second in command. Putnam had been a hero of the July 1775 Battle of Bunker Hill, and was now in charge of Long Island. It was probably while he was stationed in New Jersey, in 1777, that Burr met Theodosia Prevost (pronounced “pree-VOH.” Her husband was of Swiss-German origin). Her husband was off fighting in the southern colonies. But she herself was a patriot, siding with Washington and the Americans. Ten years older than Burr, she had married at seventeen, and had five children. She was also sick, probably with stomach cancer.

The show Hamilton is not kind to Burr, with justification. Among his other flaws, he was certainly a womanizer. But he was also extremely progressive for his time on the subject of a woman’s capacity for genius, and he fell hard for the witty and highly-educated Mrs. Prevost. And she for him. By all accounts, she was a top-notch intellect and charmer. It’s unclear exactly when their love affair began.

In December 1781, she learned that her husband, stationed in Jamaica, had died of yellow fever. She and Burr were free to marry, and did so in July of 1782. In 1783 they had a daughter, who, at Burr’s insistence, they named Theodosia. The war ended in 1783. In 1785 they had a second daughter, Sally, but she died at age three. Theodosia would be the only child of Burr’s who would reach adulthood.

He was a big fan of Mary Wollstonecraft’s A Vindication of the Rights of Woman, published in 1792, and he raised his daughter as a thoroughly educated woman of the Enlightenment. As Theodosia, his wife, grew sicker, Burr took over more and more responsibility for his daughter’s education. Theodosia-the-wife died at age 48.

Theodosia-the-daughter married a boring rich guy named Joseph Alston at age seventeen, and they had a son, whom they named Aaron Burr Alston. Sadly, he died at age eleven. A year later, in 1812, the still-grieving Theodosia set out to visit her father. The United States had just declared war against Great Britain, and Theodosia’s husband was in command of a militia in South Carolina, so he couldn’t accompany her. In December of 1812 she left Charleston on a schooner bound for New York, with only her maid and a male escort. There was a violent storm off the coast of the Carolinas, and the ship was lost at sea. She was just thirty years old.

Source: Nancy Isenberg, Fallen Founder: The Life of Aaron Burr

Mate and Create

A classic favorite movie in our house is Napoleon Dynamite, and here’s one of our favorite scenes:his drawing of a “liger.”

But were you aware that ligers really exist?

My friend Laura is one of my go-to scientists. She not only teaches AP Biology, but also POST-AP Biology, for high school seniors who can’t get enough Biology. Kids flock to take her classes. I ask her for help on pretty much all my books. (Here’s a post I did about inbred monarchs, with Laura’s help.)

So at dinner the other night, I asked her to help me define “species” for my dog book. Dogs are a subspecies of wolf, but I was getting all balled up trying to define that. It used to be so simple. A species used to be defined as similar organisms that could mate and produce fertile offspring.

But Laura explained that sometimes the barriers to reproduction to two species can be removed when habitat conditions change. “Species,” then, can be context specific. If the context changes, then two species can hybridize and become one.

For instance, explained Laura, take Lake Victoria cichlids. “Changes in light conditions due to pollution mean that two species of the genus pundamilia will mate when before they wouldn’t. Females pick mates based on their color. So in the polluted water, the females can’t tell the difference between the two species of male and will mate with either. The hybrid babies are just as fit (in the evolutionary sense–they are just as able to have babies) as mom and dad, so scientists think the two species will fuse back into one.”

In case you’re wondering, she’s talking about a genus of fish. (I had to look that up.)

What does this have to do with ligers? Well in part due to global warming, a major barrier to reproduction has been removed. Polar bears’ habitat is vanishing, so they’re moving south and mating with grizzly bears. So now there are:

Grolar Bears

Polar/Brown Bear adult hybrid. Rothschild Museum, Tring, England.

Sarah Hartwell (Messybeast) via Wikimedia Creative Commons Share-Alike

And whales and dolphins have mated and created:

Wolphins.

Second-generation wolphin female “Kawili Kai” (*23 December 2004) at Sea Life Park Hawaii, 9 months old. Offspring of first-generation wolphin female “Kekaimalu”

Photo by Mark Interrante via Wikimedia Creative Commons Share-Alike

And yes, lions and tigers have mated and created:

Ligers

Photo of male and female ligers (a liger is a cross-breed of a male lion and a female tiger) taken at Everland amusement park, South Korea.

Photo by Hkandy via Wikimedia Creative Commons Share-Alike

Here’s Laura in class, getting a surprise visit from her son, Matt, who is a “uniman.” Did I mention Laura is married to a unicorn?

That’s Harsh

I try not to discuss politics on this blog, but the widespread criticism of Hillary Clinton’s “annoying” voice begs for some historical context. The criticism tends not to be about what she is saying–it’s about how she’s saying it. You may disagree with her, or with Trump, or with Sanders. But of the three candidates, why is it Hillary’s voice that gets criticized so often?

I try not to discuss politics on this blog, but the widespread criticism of Hillary Clinton’s “annoying” voice begs for some historical context. The criticism tends not to be about what she is saying–it’s about how she’s saying it. You may disagree with her, or with Trump, or with Sanders. But of the three candidates, why is it Hillary’s voice that gets criticized so often?

A lot of commentators and news reporters comment on it. Many complain that she is loud, or shrill, or inauthentic.

Then there’s this article in the Daily Mail, which pretends to be discussing the voices of “powerful people” and how their voices grow more monotonous and higher-pitched as they get more power. But the only two “powerful people” the article discusses by name are women–Thatcher and Clinton.

Let’s go back in time–to the year 60 AD. The warrior queen of Celtic Britain, Boudica (sometimes spelled Boadicea) led a bloody rebellion against the Roman occupying forces. Roman historians were notoriously misogynistic. Cassius Dio described her as very tall (“in appearance almost terrifying”). And “a great mass of the tawniest hair fell to her hips.” But get this: “and her voice was harsh.” As Boudica’s modern biographer Antonia Fraser put it, “Condemnation of a female leader very often throws in the fact that her voice is harsh or strident.”

![By Rafesmar (Own work) [CC BY-SA 3.0 (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0)], via Wikimedia Commons](https://www.sarahalbeebooks.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/05/Boadicea_Statuary_Group-450x300.jpg)

By Rafesmar (Own work) [CC BY-SA 3.0 (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0)], via Wikimedia Commons

Cassius Dio, Roman History

Antonia Fraser, The Warrior Queens, NY: Knopf 1989, p 60 (library book)