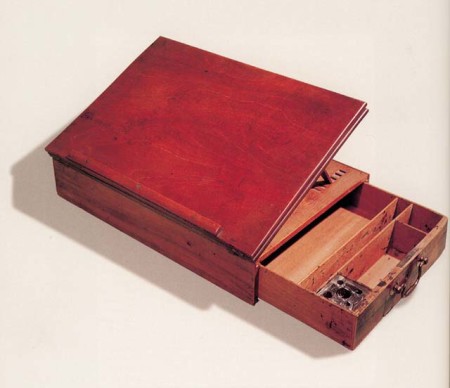

It’s been a long time since I was in high school, but I’m still in touch with my favorite teacher—who taught history, naturally—Mr. Heller. (It took me about twenty five more years to call him by his first name, Miles.) Anyway he read my blog from last week about portable writing desks and messaged me:

It’s been a long time since I was in high school, but I’m still in touch with my favorite teacher—who taught history, naturally—Mr. Heller. (It took me about twenty five more years to call him by his first name, Miles.) Anyway he read my blog from last week about portable writing desks and messaged me:

Did you ever hear of campaign furniture?

In the Am Revolution, they carried huge collapsible furniture, like chests, tables etc. with arms on them so that they could be carried. Sometime, they had to cut trees down to get the stuff through. . . . Look it up. It is pretty interesting. I can’t imagine being one of the guys who had to carry things like wardrobes.

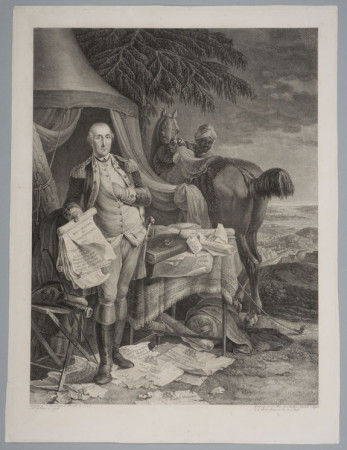

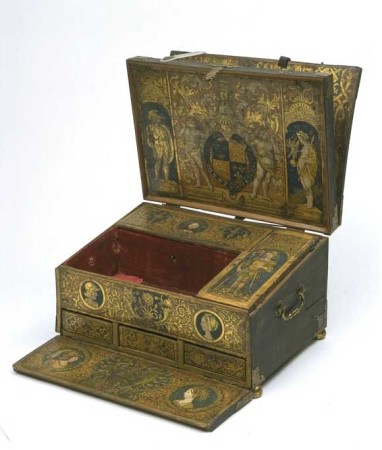

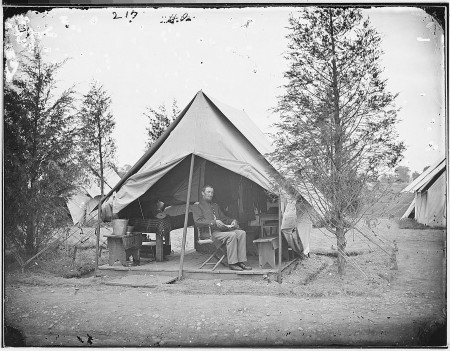

So of course I looked it up, and it’s fascinating. Campaign furniture was specially designed to be assembled and disassembled, and was made for wealthy officers to take along with them when they went to war. Officers of the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries did not pack light. They brought along dressers, dining room tables, and elegantly upholstered seating. Some even brought canopied beds. The campaign furniture varied from simple to quite ornate, and was often ingeniously designed.

In 1782, General Washington wrote to his Quartermaster, Timothy Pickering, about whether horse or ox teams ought to pull the column of officers’ baggage:

General Officers should be accommodated with Horse Teams than others, as they may frequently have occasion to make more expedition in their movements than other Officers; whereas the Baggage of the Officers of the Staff and the Line will rarely if ever be separated [sic] from the column of Baggage, on a march…

Also known as “knockdown” furniture, the trend became immensely popular with the British in India during the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. Wealthy British officers and their ladies, stationed in India, tended to be oblivious to local culture, dress, and social customs, and they dressed in clothing that was completely ill-suited to the climate. They required Western-style furniture that could accommodate stuff like tight breeches and corsets.

You can see some examples of Civil War-era knockdown furniture at this website.

You can see some examples of Civil War-era knockdown furniture at this website.

Jones, Robin D. Studies in the Decorative Arts 11.1 (2003): 137-39. Web.

Miller, Judith Furniture, page 180

Thomas Sheraton The cabinet dictionary. To which is added a supplementary treatise on geometrical lines, perspective, and painting in general 1803